This is the next post in Plan Proponent’s series on the confirmation-related recommendations in the ABI Commission Report (and, in particular, its Exiting the Case piece). We addressed Part A (section 1 and section 2) and Part B in prior posts. Part C (“Value Determinations, Allocation, and Distributions”) is more involved. Therefore, we’ll tackle it over a few posts, with this post kicking-off Part C.1: “Creditor’s Rights to Reorganization Value and Redemption Option Value.”

The Commission starts with the general observation that bankruptcy law evaluates creditor rights, with state law, the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution, and the Constitution’s Bankruptcy Clause, among other things, informing that evaluation. In particular, the Fifth Amendment, with its emphasis on property and due process, often collides, whether explicitly or implicitly, with valuation issues in bankruptcy, leading courts and practitioners to adopt different views on what it means to value a “secured creditor’s interest in the debtor’s interest in property.”

The most cited valuation concept in Chapter 11 is the rule in Section 506(a) that

value shall be determined in light of the purpose of the valuation and of the proposed disposition or use of such property, and in conjunction with any hearing on such disposition or use or on a plan affecting such creditor’s interest.

With that in mind, the Commission splits secured claim valuation into at least 3 issues:

- What is the appropriate valuation standard for the secured creditor’s collateral?

- What is the appropriate valuation standard to determine the secured creditor’s interest in the collateral?

- What is the appropriate valuation methodology for valuing the collateral?

The 3-prong valuation issue lends itself to uncertainty and, thus, litigation and/or compromise.

In the Chapter 11 plan context, if compromise or consensus is not possible, then the intersection of the “absolute priority rule” and valuation can bar a successful reorganization or leave junior creditors out of the money. We introduced the absolute priority rule here, with an emphasis on individual debtors, but it applies anytime a plan proponent must seek plan confirmation via “cramdown” under Section 1129(b) (i.e., when there is at least one dissenting class of creditors). Dating back to the 19th century, the absolute priority rule was and is intended to “prevent deals between senior creditors and equity holders that would impose unfair terms on unsecured creditors.” See Friedman v. P + P, LLC, 466 B.R. 471, 478 (9th Cir. B.A.P. 2012) (internal citations omitted).

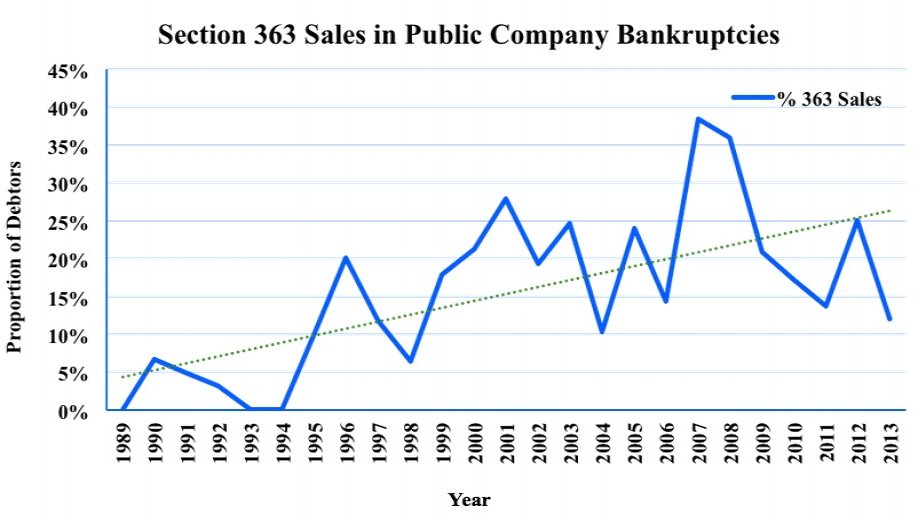

For secured claims, the Commission summarizes the absolute priority rule this way: “secured creditors have a right to receive payment in full prior to junior creditors and interest-holders receiving any value” (but see comment below). A concern of the Commission, which it addresses in its recommendations (which we’ll cover in a later post), is that the timing of the collateral valuation can cause junior creditors to “lose their rights against the estate and receive no value on account of their claims.” Meanwhile, secured creditors, who might otherwise be limited to foreclosure outside of bankruptcy, can get the benefits, if not the exclusive benefits, of the Chapter 11 case and the debtor’s going concern value. The Commission addressed a similar valuation/distribution concern in the Section 363 sale context.

Therefore, the Commission explores in Part C the rights of secured creditors and how to “best balance those rights with the reorganization needs of the debtor and the interests of the other stakeholders.” We’ll pick up next time with some of the Commission’s recommendations on valuation, in light of the above concerns.

[As an aside, does the absolute priority rule mean that a plan proponent cannot pay a dime to junior creditors and interest-holders until senior creditors are paid in full or just that senior creditors must be provided for in full? This author is not aware of anything in the Code that prohibits a plan proponent from proposing to pay a senior creditor in full over time while also making payments to a junior class in the interim, with or without consent. However, some practitioners rely on cases like Bank of Am. NT & SA v. 203 N. Lasalle St. P’ship, 526 U.S. 434 (1999) (addressing whether there is a “new value” exception to the absolute priority rule) to argue that senior claimants must receive payment in full before junior claimants can participate in a plan.]