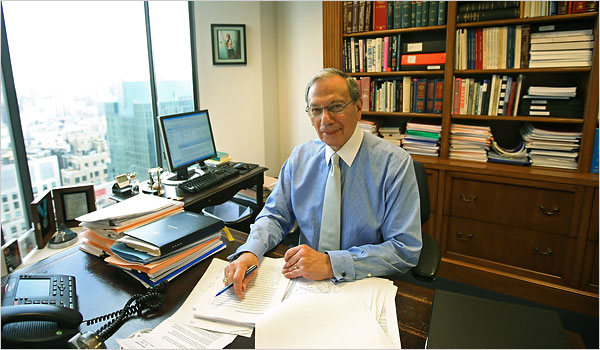

(Photo Credit: Marilynn K. Yee/The New York Times)

On my drive home from New Year’s in D.C., I learned that my buddy Doug Ford, a commercial bankruptcy attorney in Atlanta at Quirk & Quirk, LLC, had self-published his book I Do My Own Stunts: Finding My Way as an Attorney. I’m not sure how he found time to write it, but it’s an excellent read, especially Doug’s “backstory” as I’ll call it. This Atlanta-raised, Vanderbilt-educated French major’s path to law practice is fascinating to say the least. With that, we thought our readers might enjoy the following excerpt from Stunts about Doug’s 2014 Manhattan lunch with the late Harvey Miller, the architect of modern Chapter 11 practice. So here it goes, Southern debtor collector meets bankruptcy deity. Enjoy!

Excerpt from I Do My Own Stunts: Finding My Way as an Attorney (2016) by Douglas D. Ford, available on Kindle at Amazon.com:

In 2014, I had lunch with Harvey Miller, the well-known restructuring attorney, in Midtown Manhattan. He is since deceased.

Some months previous to our lunch, Mr. Miller had headlined the regional bankruptcy conference here in Atlanta, where he spoke on the current inadequacies of business reorganization law. Only someone like he could have enlivened such a topic, which he did, explaining how he thought the financial system is still at risk. When the speech was over and the program took a break, I approached him, like a moth to a flame, in order to propose a casual meeting in New York, where we were planning to visit. As I figured, all he could do was say he was too busy or ignore me, so I took a chance.

I am a commercial debt collector, involved in bankruptcy out of necessity now — no other young attorney in my firm wanted to learn it. Our matters are relatively smaller and, although sometimes complex, do not involve mortgage-backed securities or airline pilot contracts, to my knowledge. What, then, could I possibly discuss with Mr. Miller, debtor’s lead counsel in the Lehman Brothers and Delta Air Lines Chapter 11 cases, among others?

Mr. Miller accepted my proposal. That summer, I deposited my wife and daughter one morning at the Central Park Zoo and went with trepidation past the William T. Sherman Monument, feeling my Southern-ness, my anywhere-but-New-York-ness. Standing outside a nice Italian place on E. 59th in the shadow of the General Motors building at the appointed time, I saw a tall figure crossing over the street, headed my way.

The first thing Mr. Miller said was that he was watching crude oil, how much they were extracting. A prescient remark, given the recent collapse in oil. I fumbled around, told him of my love of language, offering that France might be the most fabulous trip. Italy, he quickly countered. He was cultured. If I loved the arts, he asked, why was I a lawyer? It is stimulating work, I answered, which I guess is true. He knew about Georgia, too. He told how he had once warned an Atlanta real estate investment outfit about a potential takeover threat, which later materialized. These Southern gentlemen did not fully believe that private equity out of Chicago, given an opening, would really push them out of their own operation — they were doing the “dance of death,” Mr. Miller called it, striking a macabre pose. He understood the power of leverage on a national scale, but his personal manner did not intimidate.

He knew rejection early in his career. As a Jew, he did not select bankruptcy once upon a time — it selected him. He said even Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who he knew personally, could not get a job back then at any silk-stocking firm in New York City, despite graduating first in her class at Columbia — she was not only Jewish, but also female and pregnant. I made sure I heard that correctly — I could understand this happening in the South, but in New York? The country is more uniform in its attitudes than I thought, and the past is not so long ago. To be sure, Mr. Miller talked much more about people than about law. He knew the Securities and Exchange Commission for public shareholder issues, the judges and the politics of the city for local issues. I began to understand that his success was found not so much in the letter of the law as in his understanding of everyone it affects, and in decades of hard work. “We were building something,” he said, referring to the development of a nationwide way to address the inevitable insolvency of American companies. Mr. Miller was not cynical — by the sparkle in his eyes, I could tell that he meant what he said. I began to think he was a passionate man, even a dreamer. I could relate to some of that.

He had some discontent as well. He wasn’t sure the Chapter 11 process worked that well anymore. I sensed in him concern about financial brute force, almost as though the process, the balance of equities between debtor and creditor which he had helped to engineer and which are accepted as law, were under attack. From what I understood, he felt that it has become too easy for the same private equity which once upended those Southern gentlemen to hijack bankruptcy cases by buying pieces of them and for single parties to tie things up endlessly in court to their own advantage — generally for opportunists to take control. Previously, at the conference in Atlanta, he had described standing before a packed courtroom in the Lehman case as Judge Peck declared that there was no alternative but to approve the sale of the company’s assets to another institution, that the stability of the entire financial system depended on it. I asked Mr. Miller at lunch whether people seemed to understand the importance of those proceedings while they took place, and I felt that I had asked the question poorly because of my lack of technical understanding. His exact response I cannot recall, but it was, again, not legal or technical. He had witnessed something alarming, something which the bankruptcy process itself, in its sophistication, was not able to remedy or control, despite the asset sale, and he expressed that to me. When he later testified before the House Committee on the Judiciary, Mr. Miller recounted, the political deadlock surrounding the financial industry was powerful. The problem was not one of sophistication, but one of entrenchment. Thinking of his unifying national vision, I could see how this profound yet routine division in the seat of power troubled Mr. Miller. I did not know what to say, but I felt he was disappointed in Washington. I could relate to some of that, too.

When our lunch ended, I thought highly of Harvey Miller, not so much for his legal expertise, which was superior without question, but for his human understanding and concern. He was cordial and made me feel at home in that nice Italian place. As a New York outsider, I wanted to share how Mr. Miller made a point to include me, who could provide no foreseeable insight or advantage, in his day. Far lesser attorneys have acted more self-important, in my experience, and it is an honor to have met him.

If you’d like to stay on top of important bankruptcy issues throughout the year, then you can subscribe to Plan Proponent via email here.